On Thursday 5 March 2020, the National Museum of Scotland presented Museums and Contemporary Craft, a symposium exploring how collaborations between makers and curators are shedding new light on museum collections. The day was an opportunity to hear from the contemporary makers whose practice brings heritage and new technologies together, as well as the curators working with them to uncover museum objects’ hidden histories.

Part of the Glenmorangie Research Project on Early Medieval Scotland, the symposium featured a talk by Glasgow-based designer/maker Jennifer Gray and V&A Dundee Assistant Curator Mhairi Maxwell about their collaborative work on the project in 2015. The Glenmorangie Research Project is a partnership between the National Museum of Scotland and the Glenmorangie Company - the award-winning single malt scotch whisky. Alongside exciting new research, the project also commissions makers to create objects inspired by the National Museum’s Early Medieval artefacts, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding into how these objects were made and the skills used to create them.

As part of this project, Mhairi and Jennifer worked together on the creation of a silver fitting for a drinking horn, inspired by a Pictish stone-carving of a warrior on horse-back drinking from a large drinking horn. With only a small drawing carved in stone as the starting point for their creative journey, Mhairi and Jennifer researched archeological evidence on drinking horns and Pictish silversmithing to find techniques, common motifs, and the potential designs that could have been used on a Pictish drinking horn. Their collaboration not only added to the museum’s understanding of Early Medieval silversmithing, but it also interrogated both curator and maker on ideas of authenticity and creativity, past and present.

Left: Pictish sculptured stone slab depicting a horseman with sword and shield drinking from an ox horn, from Bullion, Invergowrie, Angus, c. 900 – 950. Image courtesy of the National Museum of Scotland. Right: Jennifer Gray and Johnny Ross (Sutherland Horncraft) with the completed horns in the Creative Spirit exhibition. Photography courtesy of the National Museum of Scotland.

Left: Pictish sculptured stone slab depicting a horseman with sword and shield drinking from an ox horn, from Bullion, Invergowrie, Angus, c. 900 – 950. Image courtesy of the National Museum of Scotland. Right: Jennifer Gray and Johnny Ross (Sutherland Horncraft) with the completed horns in the Creative Spirit exhibition. Photography courtesy of the National Museum of Scotland.

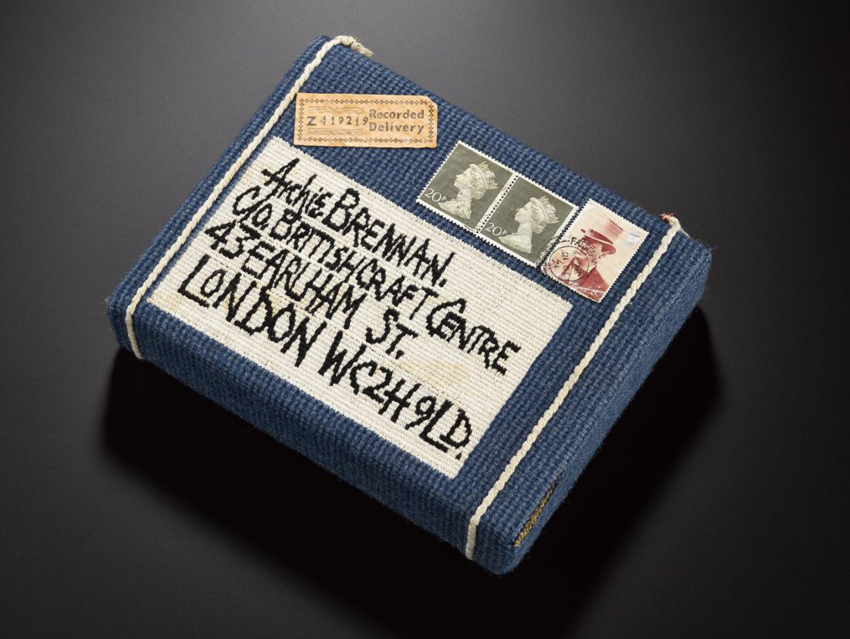

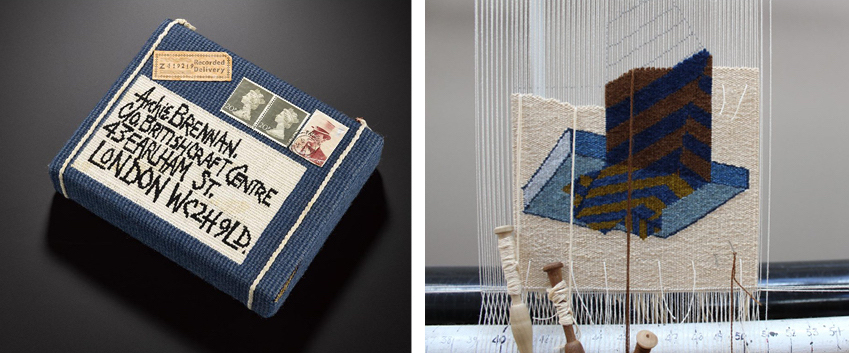

Another creative collaboration between the National Museum of Scotland and makers was presented by the Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Design Lisa Mason, and Dovecot Studios Master Weaver Naomi Robertson. The two Edinburgh institutions have been working together since 2018 on a project exploring the career and legacy of renowned Scottish weaver Archie Brennan.

Born in Roisin in 1931, Archie Brennan joined Dovecot Studios in 1943 as an apprentice, and later taught at the studios as well as Edinburgh College of Art, before moving around the world to teach tapestry weaving in Australia, Papua New Guinea, and the USA, where he lived until he died in 2019. Drawing on themes of popular culture, and art movements such as pop art, Archie contrasted the ephemeral elements of 20th century visual culture with the time-honoured medium of tapestry. He created works such as a tapestry portrait of boxer Muhammad Ali from famous press photographs, or tapestry postcards and parcels he would post to friends and galleries.

Left: Archie Brennan, Tapestry Parcel, 1974, hand woven tapestry cotton warp, wool weft, and mixed media, the National Museums Scotland. Image courtesy of the National Museums of Scotland. Right: Ben Hymers, Detail from At a Window IV: Lace Curtain (1976) after Archie Brennan, 2019, tapestry woven at Dovecot Studios. Image courtesy of Dovecot Studios.

Left: Archie Brennan, Tapestry Parcel, 1974, hand woven tapestry cotton warp, wool weft, and mixed media, the National Museums Scotland. Image courtesy of the National Museums of Scotland. Right: Ben Hymers, Detail from At a Window IV: Lace Curtain (1976) after Archie Brennan, 2019, tapestry woven at Dovecot Studios. Image courtesy of Dovecot Studios.

The research gathered by the Museum and Dovecot Studios also led to the commission of a new tapestry, with support from Creative Scotland, which will pay homage to Archie’s career. Naomi presented the weavers’ initial research and designs, as well as the two selected projects. The weavers are now working on their tapestry, with the aim to display their finished tapestries in 2021. You can follow the progress on Dovecot Studios’ social media channels.

Another major theme of the day was the relationship between craft, heritage, and new technologies. Keynote speaker Michael Eden opened the day discussing his career’s evolution from potter to digital craft artist. After learning digital printing while pursuing a Mphil at the Royal College of Art in London, Michael moved to using digital tools exclusively in his work, drawing inspiration from both museum objects and the digital world.

An example of this can be seen in Michael’s Prtlnd Vase (2012), a re-interpretation of the ancient Roman “Portland Vase” made between 5AD and 25AD. The original vase was widely reproduced by potters throughout history, and the original and subsequent versions have become popular museum objects. Often these vases have been digitised on museums’ websites to increase their reach and make the collections more accessible to a wider audience. Michael’s 3D printed interpretation of the Portland Vase plays with how the digitalisation of an object informs the way we view a piece of art, compared to in person at a museum. He presents the famous design with added pixelated details, to echo the images circulated online of the vase on museum websites and educational platforms.

Left: Michael Eden, Prtlnd Vase, 2012, 34x24cm, nylon with mineral coating, Leicester Arts and Museums Service, image courtesy of Adrian Sassoon Gallery. Right: The Portland Vase, between 5AD and 25AD, 24.5x17.7cm, Glass, The British Museum, image courtesy of the British Museum.

Left: Michael Eden, Prtlnd Vase, 2012, 34x24cm, nylon with mineral coating, Leicester Arts and Museums Service, image courtesy of Adrian Sassoon Gallery. Right: The Portland Vase, between 5AD and 25AD, 24.5x17.7cm, Glass, The British Museum, image courtesy of the British Museum.

In his opening talk, Michael noted that “objects in museums are not static”, highlighting his use of 3D printing to re-invent objects in museum collections, but also the need for makers, curators, and museum visitors to engage with collections in a more playful and dynamic way.

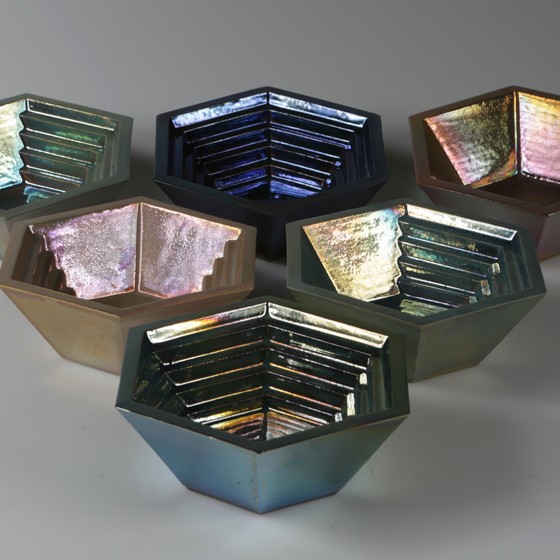

Speaking in the afternoon, London-based jewellery designer Silvia Weidenbach also talked about her involvement with museum collections, revisiting objects of the past, and using 3D printing to do so. The first V&A’s Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection Artist in Residence, Silvia uses precious stones and metal with 3D printed structures to create “volume without weight” - the ethos behind all her jewellery creations. Part of this residency at the V&A London in 2018, she created Visual Feast: a display set among, and inspired by, the stunning collection of historical treasures in the V&A’s Gilbert Collection.

The title Visual Feast came from Silvia’s own impression of the V&A's Gilbert Collection as a feast for the eyes, describing how the objects detailed craftsmanship and opulence responded to her own work and further pushed the limits of her creativity. In particular, she was charmed by a set of five highly ornamented diamond-set porcelain boxes, designed and made for Frederick II King of Prussia (1712 - 1786). Considering what ornament could mean in a contemporary setting when working with precious metals and stones together with digital printing, Silvia created Visual Feast “BOX” (box) with gold, diamonds, and mother of pearl, and a 3D printed “Moondust” - her own secret material.

Top: Silvia Weidenbach, Visual Feast BOX (box), 3D printed Moondust, gold, diamonds, mother of pearl, 2018, London and Glasgow. Image courtesy of the V&A London. Bottom: the pieces that inspired Silvia Weidenbach - left to right: Unknown maker, Snuffbox, 1765, Germany. Jean Guillaume George Krüger, Snuffbox, 1775 – 1780, Germany. Unknown maker, snuffbox, about 1765, Germany. Images courtesy of the V&A London.

The talks of the day gave me unique insights into the research and practice of the curators and makers at the forefront of contemporary craft today. The symposium concluded with a drink reception in the National Museum of Scotland’s stunning Grand Gallery, where we were invited to attend the unveiling of the inaugural Glenmorangie Commission by UK-based silversmith Simone ten Hompel – as well as given the chance to taste the award-winning Glenmorangie whisky. The evening event was also the occasion to hear more about the twelve-year partnership between the National Museum of Scotland and the Glenmorangie Company, which has allowed the Museum to undertake ground-breaking research in the history of early medieval Scotland.

Silversmith Simone ten Hompel was commissioned in 2019 to create a new piece inspired by the National Museum of Scotland’s Viking-age silver collections, to be displayed in the Making and Creating Gallery of the Museum. The resulting sculpture, Coordinate, is inspired by the Scottish landscape and the past, present, and future of the land. Driven by a desire to understand the natural landscape of Scotland and its history more deeply, Simone’s sculpture seeks to represent the physicality of Scotland as both land and idea. This new commission is part of the current phase of the Glenmorangie Research Project, called Creating Scotland, which focuses specifically on the 9th to 12th centuries and the formation of the nation state of Scotland.

While we eagerly wait until the National Museum of Scotland can re-open its doors, you can learn more about the commission and the Glenmorangie Research Project on the National Museum of Scotland’s website.

Simone ten Hompel (right) pauses with her sculpture Coordinate, silver, corten steel, guiding metal and stainless steel, 2019. Photography Jane Barlow.

Simone ten Hompel (right) pauses with her sculpture Coordinate, silver, corten steel, guiding metal and stainless steel, 2019. Photography Jane Barlow.

Read More

-

Full details→

New Talent From seaweed textiles to 3D printing, how young graduates are creating the future of craft.

In the second half of this series, textile designer Jasmine Linington and ceramicist Alison Thyra Grubb talk about sourcing seaweed to produce sustainable textiles, and the relationship between clay and digital printing.

13 Feb 2020

-

Full details→

New Talent From Cooking to Nature, New Graduates Find Inspiration Everywhere

In the first of this two-part series, meet silversmith Harriet Jenkins and textiles designer Claire Frickleton from the Craft Scotland Graduate Award 2019/20.

22 Jan 2020

-

Full details→

News Celebrating 40 years of the Scottish Glass Society

The Scottish Glass Society is celebrating 40 years through an extensive programme of exhibitions and events.

3 Oct 2019

-

Full details→

Announcement Collect 2019 Round-up

Craft Scotland returned to the Saatchi Gallery in London to showcase the very best of Scottish craftmanship. We have rounded-up the highlights from the 2019 show.

17 Jun 2019

-

Full details→

News Highlights of Spring Fling 2018

The Craft Scotland project team take a whistle-stop tour of just some of the makers' who opened their studio doors for Spring Fling 2018.

21 Jun 2018

-

Full details→

Shopping & Lifestyle Looking beyond the object

As there is now a wealth of beautiful craft available right at our fingertips, we explore the reasons why we choose to discover, own and give craft.

25 May 2018

-

Full details→

Announcement Craft Scotland Graduate Award 2018

Our new graduate award will recognise four makers from each of Scotland's art colleges who are creating high-quality work.

17 May 2018

-

Full details→

Make It Green Leading by example in ethical jewellery making

We talk to the Incorporation of Goldsmiths about their recent ethical making symposium, their new ethical making resource and how makers can make positive change.

4 May 2018

-

Full details→

![From seaweed textiles to 3D printing, how young graduates are creating the future of craft.]()

New Talent From seaweed textiles to 3D printing, how young graduates are creating the future of craft.

In the second half of this series, textile designer Jasmine Linington and ceramicist Alison Thyra Grubb talk about sourcing seaweed to produce sustainable textiles, and the relationship between clay and digital printing.

13 Feb 2020

-

Full details→

![From Cooking to Nature, New Graduates Find Inspiration Everywhere]()

New Talent From Cooking to Nature, New Graduates Find Inspiration Everywhere

In the first of this two-part series, meet silversmith Harriet Jenkins and textiles designer Claire Frickleton from the Craft Scotland Graduate Award 2019/20.

22 Jan 2020

-

Full details→

![Celebrating 40 years of the Scottish Glass Society]()

News Celebrating 40 years of the Scottish Glass Society

The Scottish Glass Society is celebrating 40 years through an extensive programme of exhibitions and events.

3 Oct 2019

-

Full details→

![Collect 2019 Round-up]()

Announcement Collect 2019 Round-up

Craft Scotland returned to the Saatchi Gallery in London to showcase the very best of Scottish craftmanship. We have rounded-up the highlights from the 2019 show.

17 Jun 2019

-

Full details→

![Highlights of Spring Fling 2018]()

News Highlights of Spring Fling 2018

The Craft Scotland project team take a whistle-stop tour of just some of the makers' who opened their studio doors for Spring Fling 2018.

21 Jun 2018

-

Full details→

![Looking beyond the object]()

Shopping & Lifestyle Looking beyond the object

As there is now a wealth of beautiful craft available right at our fingertips, we explore the reasons why we choose to discover, own and give craft.

25 May 2018

-

Full details→

![Craft Scotland Graduate Award 2018]()

Announcement Craft Scotland Graduate Award 2018

Our new graduate award will recognise four makers from each of Scotland's art colleges who are creating high-quality work.

17 May 2018

-

Full details→

![Leading by example in ethical jewellery making]()

Make It Green Leading by example in ethical jewellery making

We talk to the Incorporation of Goldsmiths about their recent ethical making symposium, their new ethical making resource and how makers can make positive change.

4 May 2018