Welcome to our new feature Make Your Own Story, a series of interviews with craft makers. Hear from makers who have fascinating stories to tell about living and working in Scotland. We hope their stories will inspire you and spark off new interpretations of craft...

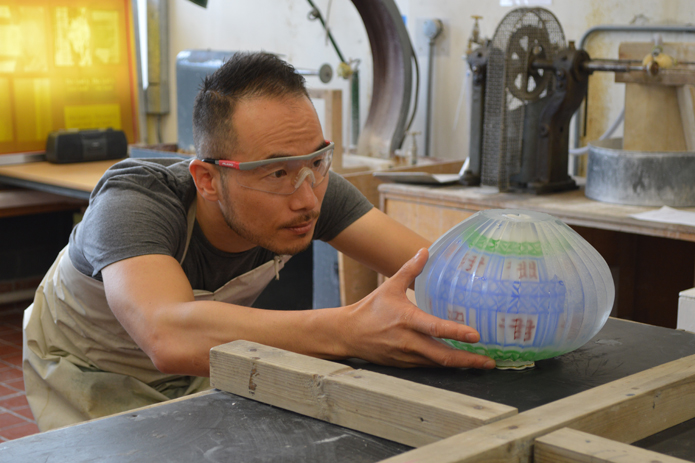

First up, we chat with Choi Keeryong, a glass artist and maker whose artistic practice has been heavily influenced by his personal cross-cultural experience of being a South Korean living in Edinburgh.

You will recognise Choi’s stunning glass work from the Scotland: Craft & Design pavilion at London Design Fair in September 2016. He has also exhibited throughout Europe; including shows at the Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh, Contemporary Applied Arts and Vessel Gallery in London.

Q: Where do you derive your inspiration from?

Choi: My artistic practice has been greatly inspired by my personal experience of being in a state of in-betweenness in both Scotland and South Korea. This state derives from my current cultural location: although I have been living and working in Edinburgh for approximately ten years, I was born, brought up and lived in South Korea for 30 years.

Inspired by the existential anguish that emerges from this experience, I explore the notion of unhomeliness (or in German unheimliche – a Freudian term that can be translated as uncanny). I think of this in a psychological and physical space, as I cannot find a sense of belonging within the existing Korean or British visual culture.

My intention for creating my work is to explore the ambiguity inherent in an individual’s cultural interpretation by attempting to stimulate a state of uncanniness (I called ‘the aesthetics of cultural uncanny’) through viewers’ visual experiences of and responses to a series of craft objects I created.

Q: Your glass technique is quite innovative, how did you end up working in this style?

Choi: Korean glass art (or the studio glass movement) developed in the 1990s. There were opportunities to undertake formal/higher-level education in South Korea in the mid-1990s, and there were postgraduate programmes in glass available about in 2000.

However, I went to university for my first degree in 1994 in ceramics and metalsmithing, and glass as an artistic medium was something I regarded as a foreign material. Yet I was attracted by the mysterious properties of glass; in 2006, I decided to explore it more in-depth.

When I was looking for an art school where I could learn glassmaking techniques, I discovered some glass artists and their artwork Alison McConachie and Dr Ray Flavell. Then I discovered they were actually teaching staff at the glass department in Edinburgh College of Art. In 2006 I started working with glass during my Masters at Edinburgh College of Art (ECA).

After completing the course, I continued working with the medium during my two-year residency at ECA. I use an inlay colouring technique during a hot glass making process that I developed when I conducted my practice-led PhD in glass (2010-2015) at the University of Edinburgh. This technique is inspired by the ancient Korean “Saggam” pottery technique and allows me to explore the state of ambiguity in a viewer’s visual experience by delineating geometric patterns and counterfeit letters onto my glass artworks; encapsulating them between the layers of transparent glass.

Q: You combine blown glass with found English teapots and other porcelain objects. Often found discarded in charity shops and flea markets, these unwanted pieces are given a new lease of life in your work. What is the significance of the found ceramics in your work?

Choi: Tea is historically and culturally very rich for both the East and West. English manufactured porcelain teapots, once of huge popularity, are used as markers in my work for this shared cultural stereotype.

Q: Can you tell us about your work inspired by tattoos?

Choi: The designs are based on the tattoos of Latin American gangsters in the USA, the meanings that different marks have, and how some of them relate back to the cultures they come from. Through this work, I am exploring the relationship between an object and surface decorations in order to promote a greater awareness of the stereotyping that can occur in relation to an individual’s visual experience with the surface decoration. In order to create a culturally (or visually) puzzling object which carries hidden meanings, I developed patterns and images based on notorious gang members’ (and criminals’) tattoos from big cities around the world.

I believe the history of the gang is often closely related to an immigration history with which I could raise a question concerning the current migrant crisis in Europe. The tattoo images were carefully manipulated and reorganised with other patterns to be viewed as a more aesthetically appealing image and to create a culturally puzzling object.

I aim to explore my artistic interest in how an object becomes a meaningful thing with its surface decoration. I look at how I might create an opportunity to induce a state of in-between-ness and provoke a range of sensitivities and feelings with an uncertain surface decoration on a glass object.

Q: How do you hope the audience will respond to your work?

Choi: The cultural ambiguity inherent in my artwork might challenge viewers, and can arouse feelings of unease when viewed. Although I deliberately choose terms such as ‘in-between’ and ‘unhomely’, which may imply negative experiences, my main artistic goal is to express psychological (or cultural) uncertainty that some immigrants may have experienced (it is not necessarily negative or positive).

That is, encounters with familiar and unfamiliar objects lead the individual to register their established logic and cognitive clarity, establishing ontological security, by defining the familiar as ‘we’ and the unfamiliar as ‘other’. I believe this dichotomous classification also dictates audience’s reactions to objects; determining whether their reactions should be ‘defensive’ or ‘acceptive’.

Thus, objects that are judged as having (cultural) in-betweenness might confuse and provoke a sense of uncertainty, leading to indecision. My artwork’s inherent distinctive qualities rely on the sense of bicultural identity present within the pieces. This bicultural identity derives from the fact that the artworks do not readily fit into either Korean or British visual culture, as they are deliberately designed to create a pseudo Korean-British or British-Korean image that can be viewed as an in-between image, or a blending of both cultures.

Go behind the scenes of Choi's work on Instagram.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Read More

-

Full details→

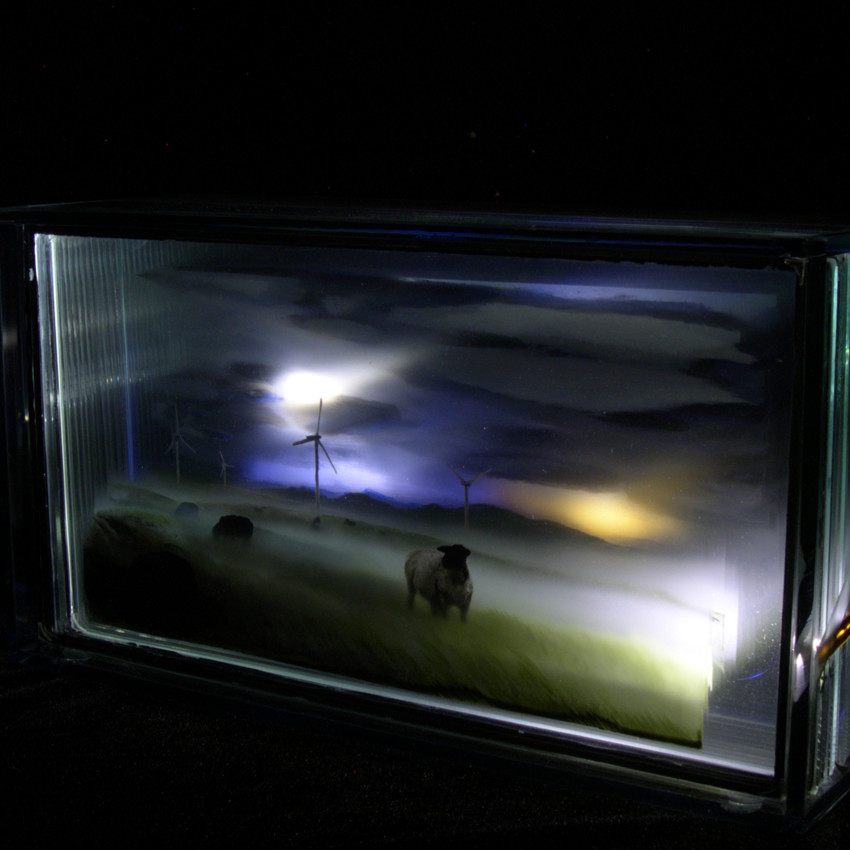

Make Your Own Story The three dimensional glass paintings of Jeff Zimmer

In this edition of Make Your Own Story, glass artist Jeff Zimmer tells us about the inspiration behind his three-dimensional glass paintings and how living in Scotland has influenced his craft.

24 Aug 2017

-

Full details→

Make Your Own Story Drawing with steel with artist blacksmith Agnes Jones

Next up in our Make Your Own Story series: we chat to Agnes Jones, an artist blacksmith who draws in steel to create wonderful pieces which are full of life.

20 Jul 2017

-

Full details→

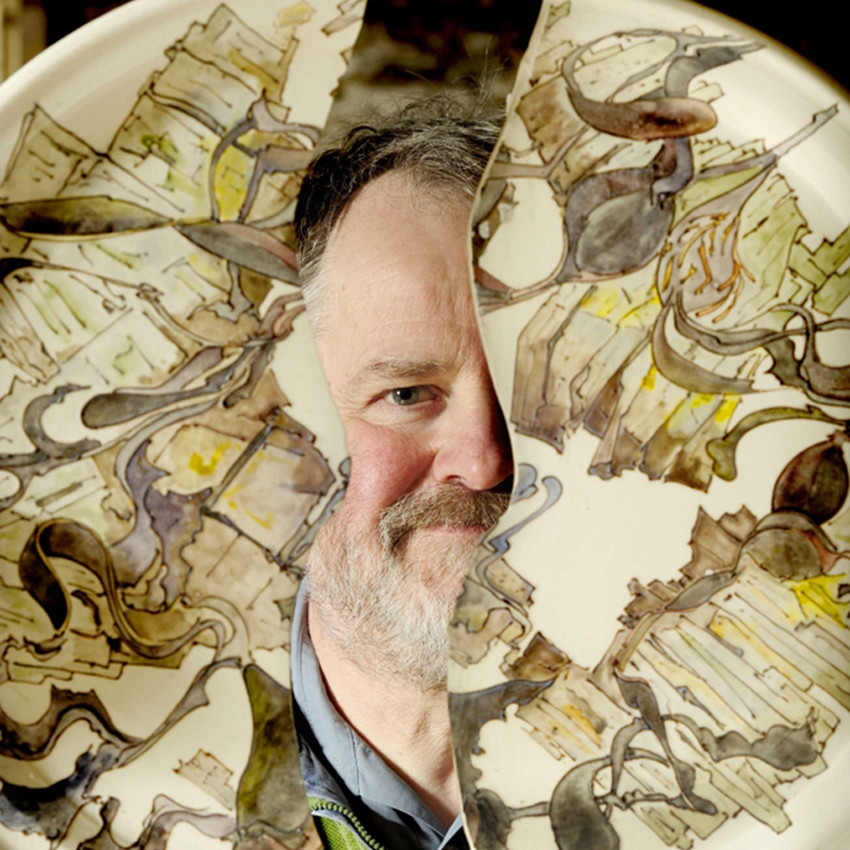

Make Your Own Story The illustrative ceramics of Peter Wareing

Peter Wareing was a designer/maker of decorative earthenware. For this instalment of Make Your Own Story, Peter spoke to us in 2017 about his practice, process and living rurally.

24 May 2017

-

Full details→

Make Your Own Story Cutting-edge jewellery artist Katharina Vones

Next up in our Make Your Own Story series we chat to Katharina Vones, who creates innovative, stimulus-responsive jewellery inspired by the idea of future ecology.

14 Mar 2017

-

Full details→

Make Your Own Story Woven textile designer Mariam Syed

We chat to Mariam Syed, a woven textile designer based in Glasgow, whose practice is influenced by the visual culture of Pakistan and mathematics.

23 Feb 2017

-

Full details→

![The three dimensional glass paintings of Jeff Zimmer]()

Make Your Own Story The three dimensional glass paintings of Jeff Zimmer

In this edition of Make Your Own Story, glass artist Jeff Zimmer tells us about the inspiration behind his three-dimensional glass paintings and how living in Scotland has influenced his craft.

24 Aug 2017

-

Full details→

![Drawing with steel with artist blacksmith Agnes Jones]()

Make Your Own Story Drawing with steel with artist blacksmith Agnes Jones

Next up in our Make Your Own Story series: we chat to Agnes Jones, an artist blacksmith who draws in steel to create wonderful pieces which are full of life.

20 Jul 2017

-

Full details→

![The illustrative ceramics of Peter Wareing]()

Make Your Own Story The illustrative ceramics of Peter Wareing

Peter Wareing was a designer/maker of decorative earthenware. For this instalment of Make Your Own Story, Peter spoke to us in 2017 about his practice, process and living rurally.

24 May 2017

-

Full details→

![Cutting-edge jewellery artist Katharina Vones]()

Make Your Own Story Cutting-edge jewellery artist Katharina Vones

Next up in our Make Your Own Story series we chat to Katharina Vones, who creates innovative, stimulus-responsive jewellery inspired by the idea of future ecology.

14 Mar 2017

-

Full details→

![Woven textile designer Mariam Syed]()

Make Your Own Story Woven textile designer Mariam Syed

We chat to Mariam Syed, a woven textile designer based in Glasgow, whose practice is influenced by the visual culture of Pakistan and mathematics.

23 Feb 2017